Natsume Soseki and Modern Japanese Literature

natsume soseki 1

natsume soseki 1

Early Life

Natsume Soseki was born Natusme Kinnosuke in the city of Edo in 1867, the year before it was renamed Tokyo. With the end of the Edo period (1603–1868), Japan would rapidly develop under the new Meiji government. The future writer was the eighth child of Natsume Naokatsu and the sixth with his wife Chie. Rather than raise the young Kinnosuke themselves, his parents sent him away to grow up with another couple who were friends of the family. The loneliness he experienced during a difficult childhood may have contributed to his later spirit of independence.

Alongside his standard education, he studied the Chinese classics and English. At the age of 17, he entered preparatory school for university. There he met Masaoka Shiki, who would become another key literary figure by modernizing the haiku. From 1890, he spent three years in the English department at the University of Tokyo.

At first, Soseki had hated English. He greatly preferred classical Chinese, and had a lifelong love of the nation’s traditional literature. In an era when many Japanese were abandoning long-established texts to study European languages, Sōseki’s classical Chinese learning was more reminiscent of an intellectual of the Edo period.

Even so, English became another string to his bow, and he learned enough of the language to begin teaching it to others while still a student. From 1893, he balanced postgraduate activities with instruction at a Tokyo teacher’s college.

Soseki, who was by then a young English teacher in the Japanese provinces, was sent to study English language and literature as part of Japan’s large-scale modernization and westernization efforts.

Travels

He arrived in London in October 1900, with great expectations, both his own and those of the Japanese government officials who sponsored his scholarship to study abroad for two years.

In London, these expectations were quickly beset by hard times: he was short of money; he lacked useful academic connections; and his terrible homesickness was exacerbated by conditions in the dreary boarding houses where he stayed.

Unable to afford to study at Cambridge or Oxford, he quickly stopped attending classes at University College London, instead choosing weekly tutorials with the eccentric Shakespeare scholar William Craig. Soseki’s unique vantage point, as one admiring of English culture but outside of and alienated from it, offers an intriguing lens through which to view late Victorian culture and society.

Soseki’s London writings depict the author as an isolated, lonely man in the midst of a bewildering city – a place of crowds, dirt, noise, and barely controlled chaos. This is not an unusual view of turn-of-the-century urban life and alienation, but Soseki’s account is intriguing in that he constructs an image of himself through comparisons with Britons, most frequently women, whom he imagines as sharing his plight. That is, though Soseki himself is alienated and isolated – and describes this in clearly racial and national terms – he sees these experiences mirrored in many of the Britons he meets.

Literary Career

Natsume Soseki departed London in Dec 1902, returning to Tokyo in Jan 1903, and started teaching at what is today’s University of Tokyo. Two years later, he made a literary splash with the publication of the first part of one of his most enduring works, I Am a Cat. It appeared in Hototogisu, a magazine launched by his friend Shiki and edited by the haiku poet Takahama Kyoshi. The warm reception of this serial novel, along with works like The Tower of London) and Botchan, made Sōseki’s name as a fiction writer.

He began to hold Thursday meetings at which literary disciples gathered, including a young Akutagawa Ryūnosuke. In 1907, he quit teaching to join the Asahi Shimbun newspaper as a full-time serialist. The move became the talk of Tokyo—at the time, leaving Japan’s top academic institution to become a professional writer was considered an extraordinary decision. Among the works he serialized in Asahi Shimbun were Sanshirō, And Then, and The Gate, which are collectively known as his first trilogy.

Sōseki was hospitalized by a stomach ulcer at the age of 43. While recuperating at a hot spring resort in Shizuoka Prefecture, his condition became critical. Friends and literary followers rushed to his sickbed, believing that he was near death.

He eventually recovered though, and in 1911 the ministry of education wasted no time in bestowing an honorary doctorate on Sōseki while he was still hale. He declined it, however, despising the contemporary spirit of studying merely to acquire such forms of recognition.

From 1912, Sōseki’s second trilogy, To the Spring Equinox and Beyond, The Wayfarer, and Kokoro was published serially in Asahi Shimbun. Around this time, his ulcer problems flared up again and his mental state deteriorated. He began a new work, Light and Darkness in 1916, but died on December 9 of the same year, leaving his final work unfinished.

Despite his central position in Japanese literature, it has taken some time for Sōseki to be recognized in the West, where he is still not as well-known as authors like Kawabata Yasunari and Mishima Yukio. His reputation has risen in recent years, however, with several new translations into English and increased research.

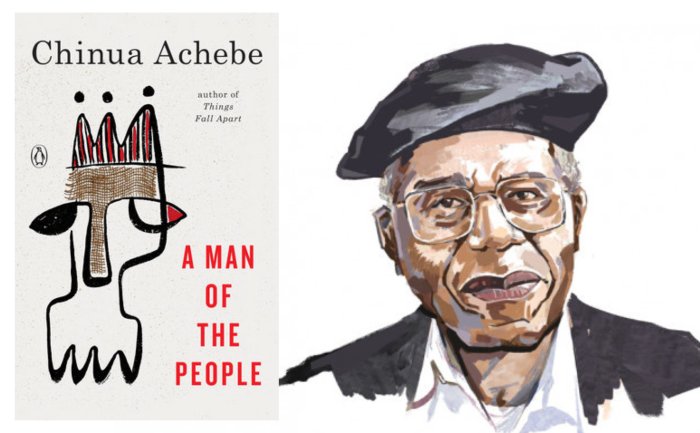

Best Natsume Soseki Books

Here are 5 Book Recommendations for the best Natsume Soseki Books to add to your reading list

Kokoro

Kokoro, meaning ‘heart’, is a tantalising novel about the friendship between a young man and an enigmatic elder whom he calls Sensei. Set in the early twentieth century, the novel enacts the transition from one generation to the next in the dynamic between Sensei, who is haunted by mysterious events in his past, and the unnamed young man, one of the new generation’s elite who will inherit the coming era.

Sanshiro

One of Soseki’s most beloved works of fiction, the novel depicts the 23-year-old Sanshiro leaving the sleepy countryside for the first time in his life to experience the constantly moving ‘real world’ of Tokyo, its women and university. In the subtle tension between our appreciation of Soseki’s lively humour and our awareness of Sanshiro’s doomed innocence, the novel comes to life. Sanshiro is also penetrating social and cultural commentary.

The Gate

The Gate describes the everyday world of the humble clerk Sosuke and his wife Oyone, living in quiet obscurity in a house at the bottom of a cliff. Seemingly cursed with the inability to have children, the couple find themselves having to take responsibility for Sosuke’s younger brother Koroku. Oyone’s health begins to fail, and news that her estranged ex-husband will be visiting nearby finally promotes a sense of crisis in Sosuke and forces him temporarily to quit his life of quiet domesticity. Highly prized for the beauty of its description of the understated love between Sosuke and Oyone, the novel has nevertheless remained in many ways mysterious.

I am a Cat

Soseki Natsume’s comic masterpiece, I Am a Cat, satirizes the foolishness of upper-middle-class Japanese society during the Meiji era. With acerbic wit and sardonic perspective, it follows the whimsical adventures of a world-weary stray kitten who comments on the follies and foibles of the people around him.

And Then

And Then tells the story of Daisuke, a man in his twenties who is struggling with his personal purpose and identity as well as the changing social landscape of Meiji-era Japan.

Daisuke’s life takes an unexpected turn when he is reunited with his college friend and his sickly wife. At first, Daisuke’s stoicism allows him to act according to his intellect, but his intellectual fortress begins to show its vulnerabilities as his emotions start to hold greater sway over his inner life. Daisuke must now weigh his choices in a culture that has always operated on the razor’s edge of societal obligation and personal freedom.

And Then is a powerful novel of an individual swept up in the floods of change.

Check out our Japanese Literature Quiz