News

Latest News Headlines from the World of Literature

- Brighton Rock by Graham Greene audiobook review – Sam West captures the menace of this modern classicby Fiona Sturges

The seaside town’s seedy underbelly is vividly evoked in this timeless tale of murder, romance and revengeWe are not short of audio versions of Brighton Rock, Graham Greene’s classic thriller from 1938 set in the eponymous seaside town. Past narrators have included Jacob Fortune‑Lloyd, Richard Brown and Tom O’Bedlam, and that’s before you get to the various radio dramatisations. But few can match this narration from the Howards End actor Samuel West, first recorded in 2011, which captures the menace and seediness that runs through Greene’s novel.It tells of 17-year-old Pinkie Brown, a razor-wielding hoodlum who is trying to cover up the murder of a journalist, Charles “Fred” Hale, killed by his gang in revenge for a story he wrote on Pinkie’s now deceased boss, Kite. Pinkie sets about wooing Rose, a naive young waitress who unwittingly saw something that could implicate him in the murder. His plan is to marry her to prevent her testifying against him. But he doesn’t bargain for the doggedness of Ida Arnold, a middle-aged lounge singer who smells of “soap and wine” and who happened to meet Hale on the day he was killed. On learning of his death, Ida refuses to believe the reports that he died of natural causes. She resolves not only to bring his killer to justice but to protect Rose from a terrible fate. Continue reading...

- New web retailer BookKind pledges 10% of all sales to charityby Ella Creamer

‘You could probably buy your books from cheaper places,’ says startup that will allow shoppers to choose between eight different charities to receive a titheA new online bookshop will donate 10% of the value of all purchases to charity.BookKind, launching on Thursday, will allow customers to pick between eight charities working across health, literacy, environment, race equality and international aid to donate to when purchasing books. Continue reading...

- A Different Kind of Power by Jacinda Ardern review – not your usual PMby Gaby Hinsliff

New Zealand’s former prime minister is a refreshingly informal narrator of her remarkable rise and fallJacinda Ardern was the future, once. New Zealand’s prime minister captured the world’s imagination with her empathetic leadership, her desire to prioritise the nation’s happiness rather than just its GDP, and her bold but deeply human approach to the early stages of the pandemic (though her “zero Covid” strategy of sealing borders to keep death rates low came back to bite her). She governed differently, resigned differently – famously saying in 2023 that she just didn’t have “enough in the tank” to fight another election – and has now written a strikingly different kind of political memoir. It opens with her sitting on the toilet clutching a pregnancy test at the height of negotiations over forming a coalition government, wondering how to tell the nation that their probable new prime minister will need maternity leave.Ardern is a disarmingly likable, warm and funny narrator, as gloriously informal on the page as she seems in person. A policeman’s daughter, raised within the Mormon church in a rural community down on its luck, she paints a vivid picture of herself as conscientious, anxious, and never really sure she was good enough for the job. In her telling at least, she became an MP almost by accident and wound up leading her party in her 30s thanks mostly to a “grinding sense of responsibility”. (Since it’s frankly impossible to believe that anyone could float this gently to the top of British politics, presumably New Zealand’s parliament is less piranha infested). Continue reading...

- British-Palestinian writer NS Nuseibeh wins Jhalak prose prize for writers of colourby Ella Creamer

‘Timely’ essay collection explores identity, religion and colonialism as Nathanael Lessore takes children’s and young adult prize and Mimi Khalvati wins for poetryBritish-Palestinian writer NS Nuseibeh has won the Jhalak prose prize for writers of colour for a “timely” and “timeless” essay collection, Namesake, which explores identity, religion and colonialism.The inaugural Jhalak poetry prize went to Mimi Khalvati for a book of collected poems, while the children’s and young adult prize was awarded to Nathanael Lessore for King of Nothing, a teen comedy about an unlikely friendship between two boys. Continue reading...

- Where to start with: Edmund Whiteby Neil Bartlett

After the news of White’s death, here is a guide to a foundational writer of gay lives and elder statesman of American queer literary fiction • Edmund White, novelist and great chronicler of gay life, dies aged 85• Edmund White remembered: ‘He was the patron saint of queer literature’Edmund White, who has died aged 85, was born in Cincinnati, to conservative, homophobic parents. Although he soon rejected almost all his family’s cultural values, he retained their work ethic: White published 36 books in his lifetime, and was working on a tale of queer life in Versailles when he died.Starting out his career in New York, during the magical and radical years that fell between gay liberation and Aids, he then worked hard and long enough to be eventually acclaimed as the “elder stateman” of American queer literary fiction. White’s most characteristic trick as a writer was to pair his impeccably “high” style with the raunchiest possible subject-matter. When talking about gay men’s sex-lives, the goods have rarely been delivered so elegantly. Author and director Neil Bartlett suggests some good places to start. Continue reading...

- Edmund White remembered: ‘He was the patron saint of queer literature’by Alan Hollinghurst, Yiyun Li, Colm Tóibín, Adam Mars-Jones, Olivia Laing, Mendez, Tom Crewe and Seán Hewitt

Colm Tóibín, Alan Hollinghurst, Adam Mars-Jones and more recall the high style and libidinous freedom of a writer who ‘was not a gateway to gay literature but a main destination’• Edmund White, novelist and great chronicler of gay life, dies aged 85 Continue reading...

- Twelve Post-War Tales by Graham Swift review – haunting visions from a Booker winnerby Elizabeth Lowry

The author’s conceptual agility is on display in these short stories surveying the trauma of conflict and the challenges of survivalThere are several wars, not all of them military ones, in these deftly turned stories from Booker winner Graham Swift. With characteristic exactness and compassion, Swift considers the cost of human conflict in all its forms – and the challenge, for those who manage to stay alive, of retrieving the past.In The Next Best Thing former Leutnant Büchner, gatekeeping civic records in postwar Germany in 1959, fields a British serviceman’s attempts to trace the fate of his German Jewish relatives during the Holocaust. Denial and guilt vie chillingly in a tale about the agony of looking back when there are only “pathetic little scraps of paper” to be found. “What did they expect, after all, what did they really hope for,” Büchner wonders, “these needy and haunted ones who still, after 15 years, kept coming forward … To be given back the actual ashes, the actual dust, the actual bones?”But she couldn’t have thought, then, what her 49-year-old self could think: that 90 years was the length of a decent human life, though rather longer, as it had proved, than her father’s. And she surely couldn’t have thought then, as she thought now, that there were two things, generally made of wood, specifically designed to accommodate the dimensions of a single human being. Two objects of carpentry. A door and a coffin. It was like the answer to a riddle. Continue reading...

- Bernardine Evaristo scoops Women’s prize outstanding contribution awardby Lucy Knight

One-off £100,000 prize awarded to Girl, Women, Other writer for entire body of work and ‘dedication to uplifting under-represented voices’Bernardine Evaristo is to receive £100,000 after being announced as the winner of the Women’s prize outstanding contribution award, a one-off prize to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Women’s prize for fiction.The author of Girl, Woman, Other and Mr Loverman has been rewarded for her entire body of work, as well as her “transformative impact on literature and her unwavering dedication to uplifting under-represented voices across the cultural landscape”.To browse books by Bernardine Evaristo visit guardianbookshop.com. Continue reading...

- We’re close to translating animal languages – what happens then?by David Farrier

AI may soon be able to decode whalespeak, among other forms of communication – but what nature has to say may not be a surpriseCharles Darwin suggested that humans learned to speak by mimicking birdsong: our ancestors’ first words may have been a kind of interspecies exchange. Perhaps it won’t be long before we join the conversation once again.The race to translate what animals are saying is heating up, with riches as well as a place in history at stake. The Jeremy Coller Foundation has promised $10m to whichever researchers can crack the code. This is a race fuelled by generative AI; large language models can sort through millions of recorded animal vocalisations to find their hidden grammars. Most projects focus on cetaceans because, like us, they learn through vocal imitation and, also like us, they communicate via complex arrangements of sound that appear to have structure and hierarchy. Continue reading...

- The best recent translated fiction – review roundupby John Self

The Propagandist by Cécile Desprairies; Lovers of Franz K by Burhan Sönmez; Back in the Day by Oliver Lovrenski; Waist Deep by Linea Maja ErnstThe Propagandist by Cécile Desprairies, translated by Natasha Lehrer (Swift, £14.99) This clever and vivid book by a historian of Vichy France falls somewhere between autobiographical novel and fictionalised memoir. It opens as a colourful story based on the author’s family: her grandmother’s morphine addiction, her aunt Zizi’s vanity (she “boasted that all she kept in her refrigerator were beauty products”), and her mother’s reluctance to talk about the past. But what were grandmother and Zizi doing in the pages of Nazi propaganda magazine Signal? The narrator learns her family were “Nazi sympathisers”, though the phrase hardly captures the zeal of her mother Lucie’s support. The details are shocking: to Lucie and her lover, “mice, rats and Jews were basically the same”, and she has no regrets after the war. “If all the French had been on the right side, Germany would have won.” Their blinkered support has lessons for today, too. “What does it matter if something is true or false,” asks one character, “if you believe it to be true?”Lovers of Franz K by Burhan Sönmez, translated by Sami Hêzil (Open Borders, £12.99) Nazi-supporting parents feature in this novel too, set in West Berlin in 1968, the year of revolutionary protests around the world. A young man of Turkish descent faces off against a police commissioner. Ferdy Kaplan is under investigation for killing a student – but his intended target was Max Brod, the executor of Franz Kafka’s estate who published Kafka’s work against his wishes. Police suspect Ferdy had an antisemitic motive against the Jewish Brod, “influenced by [his parents’] ideas”. There’s a Kafkaesque quality to the interrogation – “It is our job to assume the opposite of what you tell us,” the police say – but Kurdish author Sönmez is really interested in the question of who owns literature. Was Brod right to publish? Would Kafka be unknown if he hadn’t? The dialogue-led approach makes the book punchy and fast-moving, and brings some surprising twists before the end. Continue reading...

- What we’re reading: writers and readers on the books they enjoyed in Mayby Yiyun Li, Robert Macfarlane and Guardian readers

Writers and Guardian readers discuss the titles they have read over the last month. Join the conversation in the commentsThis past semester I taught The Voyage Out – Virginia Woolf’s first novel, which is less read and talked about than her other books – to my undergraduates. One of the most interesting things about it is that Richard and Clarissa Dalloway appear as minor characters at the beginning. In each of my rereadings (and for my students who read the novel for the first time), when the Dalloways leave, it feels as though the air pressure of the novel drops for a moment. A reader feels a longing and a wistfulness watching them disappear – a feeling that Woolf must have shared too. The Dalloways must have haunted her and waited for her to become a more mature writer. Continue reading...

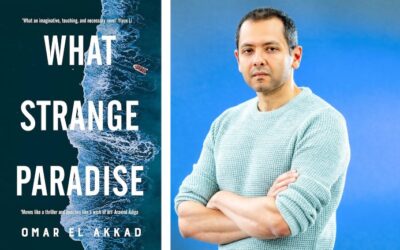

- Madeleine Thien: ‘I ran in blizzards and -20C – all I wanted was to listen to Middlemarch’by Madeleine Thien

The Canadian author on mountain running to George Eliot, powerful reminders from Omar El Akkad and the translation that brought Homer’s Iliad to lifeMy earliest reading memoryResting in my father’s arms as he read the newspaper. I must have been three or four years old. He read the paper cover to cover, and for an hour or so each night, I watched the world go by.My favourite book growing upWhen I was 11 I would go to the library downtown and request microfilm of old newspapers. I clicked the spools into place and read and read. I was horrified and baffled and amazed that there existed so many decades, so much time, in which I was … nowhere and not yet. Continue reading...