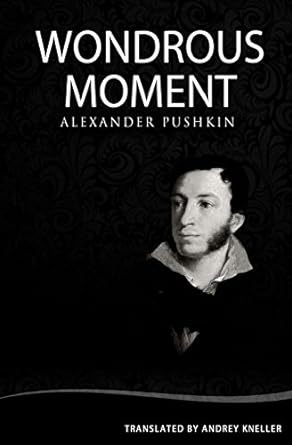

Kirdjali by Alexander Pushkin

Published in 1834, Kirdjali by Alexander Pushkin tells the tale of the soldier Kirdjali and his swashbuckling adventures.

This post may contain affiliate links that earn us a commission at no extra cost to you.

Kirdjali by Alexander Pushkin

Kirdjali by Alexander Pushkin

Kirdjali was by birth a Bulgarian.

Kirdjali, in Turkish, means a bold fellow, a knight-errant.

Kirdjali with his depredations brought terror upon the whole of Moldavia. To give some idea of him I will relate one of his exploits. One night he and the Arnout Michailaki fell together upon a Bulgarian village. They set fire to it from both ends and went from hut to hut, Kirdjali killing, while Michailaki carried off the plunder. Both cried, “Kirdjali! Kirdjali!” and the whole village ran.

When Alexander Ipsilanti proclaimed the insurrection and began raising his army, Kirdjali brought him several of his old followers. They knew little of the real object of the hetairi. But war presented an opportunity for getting rich at the expense of the Turks, and perhaps of the Moldavians too.

Alexander Ipsilanti was personally brave, but he was wanting in the qualities necessary for playing the part he had with such eager recklessness assumed. He did not know how to manage the people under his command. They had neither respect for him nor confidence.

After the unfortunate battle, when the flower of Greek youth fell, Jordaki Olimbisti advised him to retire, and himself took his place. Ipsilanti escaped to the frontiers of Austria, whence he sent his curse to the people whom he now stigmatised as mutineers, cowards, and blackguards. These cowards and blackguards mostly perished within the walls of the monastery of Seke, or on the banks of the Pruth, defending themselves desperately against a foe ten times their number.

Kirdjali belonged to the detachment commanded by George Cantacuzène, of whom might be repeated what has already been said of Ipsilanti.

On the eve of the battle near Skuliana, Cantacuzène asked permission of the Russian authorities to enter their quarters. The band was left without a commander. But Kirdjali, Sophianos, Cantagoni, and others had no need of a commander.

The battle of Skuliana seems not to have been described by any one in all its pathetic truth. Just imagine seven hundred Arnouts, Albanians, Greeks, Bulgarians, and every kind of rabble, with no notion of military art, retreating within sight of fifteen thousand Turkish cavalry. The band kept close to the banks of the Pruth, placing in front two tiny cannons, found at Jassy, in the courtyard of the Hospodar, and which had formerly been used for firing salutes on festive occasions.

The Turks would have been glad to use their cartridges, but dared not without permission from the Russian authorities; for the shots would have been sure to fly over to our banks. The commander of the Russian military post (now dead), though he had been forty years in the army, had never heard the whistle of a bullet; but he was fated to hear it now. Several bullets buzzed passed his ears. The old man got very angry and began to swear at Ohotsky, major of one of the infantry battalions. The major, not knowing what to do, ran towards the river, on the other side of which some insurgent cavalry were capering about. He shook his finger at them, on which they turned round and galloped along, with the whole Turkish army after them. The major who had shaken his finger was called Hortchevsky. I don’t know what became of him. The next day, however, the Turks attacked the Arnouts. Hot daring to use cartridges or cannon balls, they resolved, contrary to their custom, to employ cold steel. The battle was fierce. The combatants slashed and stabbed one another.

The Turks were seen with lances, which, hitherto they had never possessed, and these lances were Russian. Our Nekrassoff refugees were fighting in their ranks. The hetairi, thanks to the permission of our Emperor, were allowed to cross the Pruth and seek the protection of our garrison. They began to cross the river, Cantagoni and Sophianos being the last to quit the Turkish bank; Kirdjali, wounded the day before, was already lying in Russian quarters. Sophianos was killed. Cantagoni, a very stout man, was wounded with a spear in his stomach. With one hand he raised his sword, with the other he seized the enemy’s spear, pushed it deeper into himself, and by that means was able to reach his murderer with his own sword, when they fell together.

All was over. The Turks remained victorious, Moldavia was cleared of insurgents. About six hundred Arnouts were scattered over Bessarabia. Unable to obtain the means of subsistence, they still felt grateful to Russia for her protection. They led an idle though not a dissolute life. They could be seen in coffee-houses of half Turkish Bessarabia, with long pipes in their mouths sipping thick coffee out of small cups. Their figured Zouave jackets and red slippers with pointed toes were beginning to look shabby. But they still wore their tufted scull-cap on one side of the head; and daggers and pistols still protruded from beneath, their broad girdles. No one complained of them. It was impossible to imagine that these poor, peaceable fellows were the celebrated pikemen of Moldavia, the followers of the ferocious Kirdjali, and that he himself had been one of them.

The Pasha governing Jassy heard of all this, and, on the basis of treaty rights, requested the Russian authorities to deliver up the brigand. The police made inquiries, and found that Kirdjali really was at Kishineff. They captured him in the house of a runaway monk in the evening, while he was at supper, sitting in the twilight with seven comrades.

Kirdjali was arraigned. He did not attempt to conceal the truth. He owned he was Kirdjali.

“But,” he added, “since I crossed the Pruth, I have not touched a hair of property that did not belong to me, nor have I cheated the meanest gipsy. To the Turks, the Moldavians, and the Walachians I am certainly a brigand, but to the Russians a guest. When Sophianos, after exhausting all his cartridges, came over here, he collected buttons from the uniforms, nails, watch-chains, and nobs from the daggers for the final discharge, and I myself handed him twenty beshléks to fire off, leaving myself without money. God is my witness that I, Kirdjali, lived by charity. Why then do the Russians now hand me over to my enemies?”

After that Kirdjali was silent, and quietly awaited his fate. It was soon announced to him. The authorities, not thinking themselves hound to look upon brigandage from its romantic side, and admitting the justice of the Turkish demand, ordered Kirdjali to be given up that he might be sent to Jassy.

A man of brains and feeling, at that time young and unknown, but now occupying an important post, gave me a graphic description of Kirdjali’s departure.

“At the gates of the prison,” he said, “stood a hired karutsa. Perhaps you don’t know what a karutsa is? It is a low basket-carriage, to which quite recently used to be harnessed six or eight miserable screws. A Moldavian, with a moustache and a sheepskin hat, sitting astride one of the horses, cried out and cracked his whip every moment, and his wretched little beasts went on at a sharp trot. If one of them began to lag, then he unharnessed it with terrific cursing and left it on the road, not caring what became of it. On the return journey he was sure to find them in the same place, calmly grazing on the steppes. Frequently a traveller starting from a station with eight horses would arrive at the next with a pair only. It was so about fifteen years ago. Now in Russianized Bessarabia, Russian harness and Russian telegas (carts) have been adopted.

“Such a karutsa as I have described stood at the gate of the jail in 1821, towards the end of September. Jewesses with their sleeves hanging down and with flapping slippers, Arnouts in ragged but picturesque costumes, stately Moldavian women with black-eyed children in their arms, surrounded the harutsa. The men maintained silence. The women were excited, as if expecting something to happen.

“The gates opened, and several police officers stepped into the street, followed by two soldiers leading Kirdjali in chains.

“He looked about thirty. The features of his dark face were regular and austere. He was tall, broad-shouldered, and seemed to possess great physical strength. He wore a variegated turban on the side of his head, and a broad sash round his slender waist. A dolman of thick, dark blue cloth, the wide plaits of his over-shirt falling just above the knees, and a pair of handsome slippers completed his dress. His bearing was calm and haughty.

“One of the officials, a red-faced old man in a faded uniform, with three buttons hanging loose, a pair of lead spectacles which pinched a crimson knob doing duty for a nose, unrolled a paper, and stooping, began to read in the Moldavian tongue. From time to time he glanced haughtily at the handcuffed Kirdjali, to whom apparently the document referred. Kirdjali listened attentively. The official finished his reading, folded the paper, and called out sternly to the people, ordering them to make way for the karutsa to drive up. Then Kirdjali, turning towards him, said a few words in Moldavian; his voice trembled, his countenance changed, he burst into tears, and fell at the feet of the police officer, with a clanking of his chains. The police officer, in alarm, started back; the soldiers were going to raise Kirdjali, but he got up of his own accord, gathered up his chains, and stepping into the harutsa, cried egaida!’

“The gens d’armes got in by his side, the Moldavian cracked his whip, and the karutsa rolled away.

“What was Kirdjali saying to you? inquired a young official of the police officer.

“He asked me,” replied the officer, smiling, “to take care of his wife and child, who live a short distance from Kilia, in a Bulgarian village; he is afraid they might suffer through him. The rabble are so ignorant!'”

The young official’s story affected me greatly. I was sorry for poor Kirdjali. For a long while I knew nothing of his fate. Many years afterwards I met the young official. We began talking of old times.

“How about your friend Kirdjali?” I asked. “Do you know what became of him?”

“Of course I do,” he replied, and he told me the following.

After being brought to Jassy, Kirdjali was taken before the Pasha, who condemned him to be impaled. The execution was postponed till some feast day. Meanwhile he was put in confinement. The prisoner was guarded by seven Turks—common people, and at the bottom of their hearts brigands like himself. They respected him and listened with the eagerness of true orientals to his wonderful stories. Between the guards and their prisoner a close friendship sprang up. On one occasion Kirdjali said to them:

“Brothers! My hour is near. No one can escape his doom. I shall soon part from you, and I should like to leave you something in remembrance of me.” The Turks opened their ears.

“Brothers;” added Kirdjali, “three years back, when I was engaged in brigandage with the late Mihailaki, we buried in the Steppes, not far from Jassy, a kettle with some coins in it. Seemingly, neither he nor I will ever possess that treasure. So be it; take it to yourselves and divide it amicably.”

The Turks nearly went crazy. They began considering how they could find the spot so vaguely indicated. They thought and thought, and at last decided that Kirdjali must himself show them.

Night set in. The Turks took off the fetters that weighed upon the prisoner’s feet, hound his hands with a rope, and taking him with them, started for the Steppes. Kirdjali led them, going in a straight line from one mound to another. They walked about for some time. At last Kirdjali stopped close to a broad stone, measured a dozen steps to the south, stamped, and said, “Here.”

The Turks arranged themselves for work. Four took out their daggers and began digging the earth, while three remained on guard. Kirdjali sat down on the stone, and looked on.

“Well, now, shall you be long?” he inquired; “have you found it?”

“Not yet,” replied the Turks, and they worked away till the perspiration rolled like hail from them.

Kirdjali grew impatient.

“What people!” he exclaimed; “they can’t even dig decently. Why, I should have found it in two minutes. Children! Untie my hands, and give me a dagger.”

The Turks reflected, and began to consult with one another.

“Why not?” they concluded. “We will release his hands, and give him a dagger. What can it matter? He is only one, while we are seven.”

And the Turks unbound his bands and gave him a dagger.

At last Kirdjali was free and armed. What must have been his sensations. He began digging rapidly, the guard assisting. Suddenly he thrust his dagger into one of them, leaving the blade sticking in the man’s breast; he snatched from his girdle a couple of pistols.

The remaining six, seeing Kirdjali armed with two pistols, ran away.

Kirdjali is now carrying on his brigandage near Jassy. Not long ago he wrote to the Hospodar, demanding from him five thousand louis, and threatening, in the event of the money not being paid, to set fire to Jassy, and to reach the Hospodar himself. The five thousand louis were forwarded to him.

A fine fellow Kirdjali!

Best Alexander Pushkin Books to Read

If you enjoyed Kirdjali by Alexander Pushkin, check out The Schoolmaster by Anton Chekhov

Narrated by Daniel Davison, courtesy of Libravox.org