The Cauldron of Oil by Wilkie Collins

The Cauldron of Oil by Wilkie Collins appeared in the collection My Miscellanies Vol II published in 1863.

This post may contain affiliate links that earn us a commission at no extra cost to you.

The Cauldron of Oil by Wilkie Collins

The Cauldron of Oil by Wilkie Collins

This post may contain affiliate links that earn us a commission at no extra cost to you.

About one French league distant from the city of Toulouse, there is a village called Croix-Daurade. In the military history of England, this place is associated with a famous charge of the eighteenth hussars, which united two separated columns of the British army, on the day before the Duke of Wellington fought the battle of Toulouse. In the criminal history of France, the village is memorable as the scene of a daring crime, which was discovered and punished under circumstances sufficiently remarkable to merit preservation in the form of a plain narrative.

I. The Persons of the Drama.

In the year seventeen hundred, the resident priest of the village of Croix-Daurade was Monsieur Pierre-Célestin Chaubard. He was a man of no extraordinary energy or capacity, simple in his habits, and sociable in his disposition. His character was irreproachable; he was strictly conscientious in the performance of his duties; and he was universally respected and beloved by all his parishioners.

Among the members of his flock, there was a family named Siadoux. The head of the household, Saturnin Siadoux, had been long established in business at Croix-Daurade as an oil-manufacturer. At the period of the events now to be narrated, he had attained the age of sixty, and was a widower. His family consisted of five children—three young men, who helped him in the business, and two daughters. His nearest living relative was his sister, the widow Mirailhe.

The widow resided principally at Toulouse. Her time in that city was mainly occupied in winding up the business affairs of her deceased husband, which had remained unsettled for a considerable period after his death, through delays in realising certain sums of money owing to his representative. The widow had been left very well provided for—she was still a comely attractive woman—and more than one substantial citizen of Toulouse had shown himself anxious to persuade her into marrying for the second time.

But the widow Mirailhe lived on terms of great intimacy and affection with her brother Siadoux and his family; she was sincerely attached to them, and sincerely unwilling, at her age, to deprive her nephews and nieces, by a second marriage, of the inheritance, or even of a portion of the inheritance, which would otherwise fall to them on her death. Animated by these motives, she closed her doors resolutely on all suitors who attempted to pay their court to her, with the one exception of a master-butcher of Toulouse, whose name was Cantegrel.

This man was a neighbour of the widow’s, and had made himself useful by assisting her in the business complications which still hung about the realisation of her late husband’s estate. The preference which she showed for the master-butcher was, thus far, of the purely negative kind. She gave him no absolute encouragement; she would not for a moment admit that there was the slightest prospect of her ever marrying him—but, at the same time, she continued to receive his visits, and she showed no disposition to restrict the neighbourly intercourse between them, for the future, within purely formal bounds.

Under these circumstances, Saturnin Siadoux began to be alarmed, and to think it time to bestir himself. He had no personal acquaintance with Cantegrel, who never visited the village; and Monsieur Chaubard (to whom he might otherwise have applied for advice) was not in a position to give an opinion: the priest and the master-butcher did not even know each other by sight. In this difficulty, Siadoux bethought himself of inquiring privately at Toulouse, in the hope of discovering some scandalous passages in Cantegrel’s early life, which might fatally degrade him in the estimation of the widow Mirailhe.

The investigation, as usual in such cases, produced rumours and reports in plenty, the greater part of which dated back to a period of the butcher’s life when he had resided in the ancient town of Narbonne. One of these rumours, especially, was of so serious a nature, that Siadoux determined to test the truth or falsehood of it, personally, by travelling to Narbonne. He kept his intention a secret not only from his sister and his daughters, but also from his sons; they were young men, not over-patient in their tempers—and he doubted their discretion. Thus, nobody knew his real purpose but himself, when he left home.

His safe arrival at Narbonne was notified in a letter to his family. The letter entered into no particulars relating to his secret errand: it merely informed his children of the day when they might expect him back, and of certain social arrangements which he wished to be made to welcome him on his return. He proposed, on his way home, to stay two days at Castelnaudry, for the purpose of paying a visit to an old friend who was settled there.

According to this plan, his return to Croix-Daurade would be deferred until Tuesday, the twenty-sixth of April, when his family might expect to see him about sunset, in good time for supper. He further desired that a little party of friends might be invited to the meal, to celebrate the twenty-sixth of April (which was a feast-day in the village), as well as to celebrate his return. The guests whom he wished to be invited were, first, his sister; secondly, Monsieur Chaubard, whose pleasant disposition made him a welcome guest at all the village festivals; thirdly and fourthly, two neighbours, business-men like himself, with whom he lived on terms of the friendliest intimacy.

That was the party; and the family of Siadoux took especial pains, as the time approached, to provide a supper worthy of the guests, who had all shown the heartiest readiness in accepting their invitations.

This was the domestic position, these were the family prospects, on the morning of the twenty-sixth of April—a memorable day, for years afterwards, in the village of Croix-Daurade.

II. The Events of the Day.

Besides the curacy of the village church, good Monsieur Chaubard held some small ecclesiastical preferment in the cathedral church of St. Stephen at Toulouse. Early in the forenoon of the twenty-sixth, certain matters connected with this preferment took him from his village curacy to the city—a distance which has been already described as not greater than one French league, or between two and three English miles.

After transacting his business, Monsieur Chaubard parted with his clerical brethren, who left him by himself in the sacristy (or vestry) of the church. Before he had quitted the room, in his turn, the beadle entered it, and inquired for the Abbé de Mariotte, one of the officiating priests attached to the cathedral.

“The Abbé has just gone out,” replied Monsieur Chaubard. “Who wants him?”

“A respectable-looking man,” said the beadle. “I thought he seemed to be in some distress of mind, when he spoke to me.”

“Did he mention his business with the Abbé?”

“Yes, sir; he expressed himself as anxious to make his confession immediately.”

“In that case,” said Monsieur Chaubard, “I may be of use to him in the Abbé’s absence—for I have authority to act here as confessor. Let us go into the church, and see if this person feels disposed to accept my services.”

When they went into the church, they found the man walking backwards and forwards in a restless, disordered manner. His looks were so strikingly suggestive of some serious mental perturbation, that Monsieur Chaubard found it no easy matter to preserve his composure, when he first addressed himself to the stranger.

“I am sorry,” he began, “that the Abbé de Mariotte is not here to offer you his services——”

“I want to make my confession,” said the man, looking about him vacantly, as if the priest’s words had not attracted his attention.

“You can do so at once, if you please,” said Monsieur Chaubard. “I am attached to this church, and I possess the necessary authority to receive confessions in it. Perhaps, however, you are personally acquainted with the Abbé de Mariotte? Perhaps you would prefer waiting——”

“No!” said the man, roughly. “I would as soon, or sooner, confess to a stranger.”

“In that case,” replied Monsieur Chaubard, “be so good as to follow me.”

He led the way to the confessional. The beadle, whose curiosity was excited, waited a little, and looked after them. In a few minutes, he saw the curtains, which were sometimes used to conceal the face of the officiating priest, suddenly drawn. The penitent knelt with his back turned to the church. There was literally nothing to see—but the beadle waited nevertheless, in expectation of the end.

After a long lapse of time, the curtain was withdrawn, and priest and penitent left the confessional.

The change which the interval had worked in Monsieur Chaubard was so extraordinary, that the beadle’s attention was altogether withdrawn, in the interest of observing it, from the man who had made the confession. He did not remark by which door the stranger left the church—his eyes were fixed on Monsieur Chaubard. The priest’s naturally ruddy face was as white as if he had just risen from a long sickness—he looked straight before him, with a stare of terror—and he left the church as hurriedly as if he had been a man escaping from prison; left it without a parting word, or a farewell look, although he was noted for his courtesy to his inferiors on all ordinary occasions.

“Good Monsieur Chaubard has heard more than he bargained for,” said the beadle, wandering back to the empty confessional, with an interest which he had never felt in it till that moment.

The day wore on as quietly as usual in the village of Croix-Daurade. At the appointed time, the supper-table was laid for the guests in the house of Saturnin Siadoux. The widow Mirailhe, and the two neighbours, arrived a little before sunset. Monsieur Chaubard, who was usually punctual, did not make his appearance with them; and when the daughters of Saturnin Siadoux looked out from the upper windows, they saw no signs on the high road of their father’s return.

Sunset came—and still neither Siadoux nor the priest appeared. The little party sat waiting round the table, and waited in vain. Before long, a message was sent up from the kitchen, representing that the supper must be eaten forthwith, or be spoilt; and the company began to debate the two alternatives, of waiting, or not waiting, any longer.

“It is my belief,” said the widow Mirailhe, “that my brother is not coming home to-night. When Monsieur Chaubard joins us, we had better sit down to supper.”

“Can any accident have happened to my father?” asked one of the two daughters, anxiously.

“God forbid!” said the widow.

“God forbid!” repeated the two neighbours, looking expectantly at the empty supper-table.

“It has been a wretched day for travelling,” said Louis, the eldest son.

“It rained in torrents, all yesterday,” added Thomas, the second son.

“And your father’s rheumatism makes him averse to travelling in wet weather,” suggested the widow, thoughtfully.

“Very true!” said the first of the two neighbours, shaking his head piteously at his passive knife and fork.

Another message came up from the kitchen, and peremptorily forbade the company to wait any longer.

“But where is Monsieur Chaubard?” said the widow. “Has he been taking a journey too? Why is he absent? Has anybody seen him to-day?”

“I have seen him to-day,” said the youngest son, who had not spoken yet. This young man’s name was Jean; he was little given to talking, but he had proved himself, on various domestic occasions, to be the quickest and most observant member of the family.

“Where did you see him?” asked the widow.

“I met him, this morning, on his way into Toulouse.”

“He has not fallen ill, I hope? Did he look out of sorts when you met him?”

“He was in excellent health and spirits,” said Jean. “I never saw him look better——”

“And I never saw him look worse,” said the second of the neighbours, striking into the conversation with the aggressive fretfulness of a hungry man.

“What! this morning?” cried Jean, in astonishment.

“No; this afternoon,” said the neighbour. “I saw him going into our church here. He was as white as our plates will be—when they come up. And what is almost as extraordinary, he passed without taking the slightest notice of me.”

Jean relapsed into his customary silence. It was getting dark; the clouds had gathered while the company had been talking; and, at the first pause in the conversation, the rain, falling again in torrents, made itself drearily audible.

“Dear, dear me!” said the widow. “If it was not raining so hard, we might send somebody to inquire after good Monsieur Chaubard.”

“I’ll go and inquire,” said Thomas Siadoux. “It’s not five minutes’ walk. Have up the supper; I’ll take a cloak with me; and if our excellent Monsieur Chaubard is out of his bed, I’ll bring him back, to answer for himself.”

With those words he left the room. The supper was put on the table forthwith. The hungry neighbour disputed with nobody from that moment, and the melancholy neighbour recovered his spirits.

On reaching the priest’s house, Thomas Siadoux found him sitting alone in his study. He started to his feet, with every appearance of the most violent alarm, when the young man entered the room.

“I beg your pardon, sir,” said Thomas; “I am afraid I have startled you.”

“What do you want?” asked Monsieur Chaubard, in a singularly abrupt, bewildered manner.

“Have you forgotten, sir, that this is the night of our supper?” remonstrated Thomas. “My father has not come back; and we can only suppose——”

At those words the priest dropped into his chair again, and trembled from head to foot. Amazed to the last degree by this extraordinary reception of his remonstrance, Thomas Siadoux remembered, at the same time, that he had engaged to bring Monsieur Chaubard back with him; and, he determined to finish his civil speech, as if nothing had happened.

“We are all of opinion,” he resumed, “that the weather has kept my father on the road. But that is no reason, sir, why the supper should be wasted, or why you should not make one of us, as you promised. Here is a good warm cloak——”

“I can’t come,” said the priest. “I’m ill; I’m in bad spirits; I’m not fit to go out.” He sighed bitterly, and hid his face in his hands.

“Don’t say that, sir,” persisted Thomas. “If you are out of spirits, let us try to cheer you. And you, in your turn, will enliven us. They are all waiting for you at home. Don’t refuse, sir,” pleaded the young man, “or we shall think we have offended you, in some way. You have always been a good friend to our family——”

Monsieur Chaubard again rose from his chair, with a second change of manner, as extraordinary and as perplexing as the first. His eyes moistened as if the tears were rising in them; he took the hand of Thomas Siadoux, and pressed it long and warmly in his own. There was a curious mixed expression of pity and fear in the look which he now fixed on the young man.

“Of all the days in the year,” he said, very earnestly, “don’t doubt my friendship to-day. Ill as I am, I will make one of the supper-party, for your sake——”

“And for my father’s sake?” added Thomas, persuasively.

“Let us go to the supper,” said the priest.

Thomas Siadoux wrapped the cloak round him, and they left the house.

Every one at the table noticed the change in Monsieur Chaubard. He accounted for it by declaring, confusedly, that he was suffering from nervous illness; and then added that he would do his best, notwithstanding, to promote the social enjoyment of the evening. His talk was fragmentary, and his cheerfulness was sadly forced; but he contrived, with these drawbacks, to take his part in the conversation—except in the case when it happened to turn on the absent master of the house. Whenever the name of Saturnin Siadoux was mentioned—either by the neighbours, who politely regretted that he was not present; or by the family, who naturally talked about the resting-place which he might have chosen for the night—Monsieur Chaubard either relapsed into blank silence, or abruptly changed the topic. Under these circumstances, the company, by whom he was respected and beloved, made the necessary allowances for his state of health; the only person among them, who showed no desire to cheer the priest’s spirits, and to humour him in his temporary fretfulness, being the silent younger son of Saturnin Siadoux.

Both Louis and Thomas noticed that, from the moment when Monsieur Chaubard’s manner first betrayed his singular unwillingness to touch on the subject of their father’s absence, Jean fixed his eyes on the priest, with an expression of suspicious attention; and never looked away from him for the rest of the evening. The young man’s absolute silence at table did not surprise his brothers, for they were accustomed to his taciturn habits. But the sullen distrust betrayed in his close observation of the honoured guest and friend of the family, surprised and angered them. The priest himself seemed once or twice to be aware of the scrutiny to which he was subjected, and to feel uneasy and offended, as he naturally might. He abstained, however, from openly noticing Jean’s strange behaviour; and Louis and Thomas were bound, therefore, in common politeness, to abstain from noticing it also.

The inhabitants of Croix-Daurade kept early hours. Towards eleven o’clock, the company rose and separated for the night. Except the two neighbours, nobody had enjoyed the supper, and even the two neighbours, having eaten their fill, were as glad to get home as the rest. In the little confusion of parting, Monsieur Chaubard completed the astonishment of the guests at the extraordinary change in him, by slipping away alone, without waiting to bid anybody good night.

The widow Mirailhe and her nieces withdrew to their bed-rooms, and left the three brothers by themselves in the parlour.

“Jean,” said Thomas Siadoux, “I have a word to say to you. You stared at our good Monsieur Chaubard in a very offensive manner all through the evening. What did you mean by it?”

“Wait till to-morrow,” said Jean; “and perhaps I may tell you.”

He lit his candle, and left them. Both the brothers observed that his hand trembled, and that his manner—never very winning—was, on that night, more serious and more unsociable than usual.

III. The Younger Brother.

When post-time came on the morning of the twenty-seventh, no letter arrived from Saturnin Siadoux. On consideration, the family interpreted this circumstance in a favourable light. If the master of the house had not written to them, it followed, surely, that he meant to make writing unnecessary by returning on that day.

As the hours passed, the widow and her nieces looked out, from time to time, for the absent man. Towards noon, they observed a little assembly of people approaching the village. Ere long, on a nearer view, they recognised at the head of the assembly, the chief magistrate of Toulouse, in his official dress. He was accompanied by his Assessor (also in official dress), by an escort of archers, and by certain subordinates attached to the town-hall. These last appeared to be carrying some burden, which was hidden from view by the escort of archers. The procession stopped at the house of Saturnin Siadoux; and the two daughters, hastening to the door, to discover what had happened, met the burden which the men were carrying, and saw, stretched on a litter, the dead body of their father.

The corpse had been found that morning on the banks of the river Lers. It was stabbed in eleven places with knife or dagger wounds. None of the valuables about the dead man’s person had been touched; his watch and his money were still in his pockets. Whoever had murdered him, had murdered him for vengeance, not for gain.

Some time elapsed before even the male members of the family were sufficiently composed to hear what the officers of justice had to say to them. When this result had been at length achieved, and when the necessary inquiries had been made, no information of any kind was obtained which pointed to the murderer, in the eye of the law. After expressing his sympathy, and promising that every available means should be tried to effect the discovery of the criminal, the chief magistrate gave his orders to his escort, and withdrew.

When night came, the sister and the daughters of the murdered man retired to the upper part of the house, exhausted by the violence of their grief. The three brothers were left once more alone in the parlour, to speak together of the awful calamity which had befallen them. They were of hot Southern blood, and they looked on one another with a Southern thirst for vengeance in their tearless eyes.

The silent younger son was now the first to open his lips.

“You charged me yesterday,” he said to his brother Thomas, “with looking strangely at Monsieur Chaubard all the evening; and I answered that I might tell you why I looked at him when to-morrow came. To-morrow has come, and I am ready to tell you.”

He waited a little, and lowered his voice to a whisper when he spoke again.

“When Monsieur Chaubard was at our supper-table last night,” he said, “I had it in my mind that something had happened to our father, and that the priest knew it.”

The two elder brothers looked at him in speechless astonishment.

“Our father has been brought back to us a murdered man!” Jean went on, still in a whisper. “I tell you, Louis—and you, Thomas—that the priest knows who murdered him.”

Louis and Thomas shrank from their younger brother, as if he had spoken blasphemy.

“Listen,” said Jean. “No clue has been found to the secret of the murder. The magistrate has promised us to do his best—but I saw in his face that he had little hope. We must make the discovery ourselves—or our father’s blood will have cried to us for vengeance, and cried in vain. Remember that—and mark my next words. You heard me say yesterday evening, that I had met Monsieur Chaubard on his way to Toulouse in excellent health and spirits. You heard our old friend and neighbour contradict me at the supper-table, and declare that he had seen the priest, some hours later, go into our church here with the face of a panic-stricken man. You saw, Thomas, how he behaved when you went to fetch him to our house. You saw, Louis, what his looks were like when he came in. The change was noticed by everybody—what was the cause of it? I saw the cause in the priest’s own face, when our father’s name turned up in the talk round the supper-table. Did Monsieur Chaubard join in that talk? He was the only person present who never joined in it once. Did he change it, on a sudden, whenever it came his way? It came his way four times; and four times he changed it—trembling, stammering, turning whiter and whiter, but still, as true as the Heaven above us, shifting the talk off himself, every time! Are you men? Have you brains in your heads? Don’t you see, as I see, what this leads to? On my salvation I swear it—the priest knows the hand that killed our father!”

The faces of the two elder brothers darkened vindictively, as the conviction of the truth fastened itself on their minds.

“How could he know it?” they inquired, eagerly.

“He must tell us himself,” said Jean.

“And if he hesitates—if he refuses to open his lips?”

“We must open them by main force.”

They drew their chairs together after that last answer, and consulted, for some time, in whispers.

When the consultation was over, the brothers rose and went into the room where the dead body of their father was laid out. The three kissed him, in turn, on the forehead—then took hands together, and looked, meaningly, in each other’s faces—then separated. Louis and Thomas put on their hats, and went at once to the priest’s residence; while Jean withdrew by himself to the great room at the back of the house, which was used for the purposes of the oil-factory.

Only one of the workmen was left in the place. He was watching an immense cauldron of boiling linseed-oil.

“You can go home,” said Jean, patting the man kindly on the shoulder. “There is no hope of a night’s rest for me, after the affliction that has befallen us—I will take your place at the cauldron. Go home, my good fellow—go home.”

The man thanked him, and withdrew. Jean followed, and satisfied himself that the workman had really left the house. He then returned, and sat down by the boiling cauldron.

Meanwhile, Louis and Thomas presented themselves at the priest’s house. He had not yet retired to bed, and he received them kindly—but with the same extraordinary agitation in his face and manner which had surprised all who saw him on the previous day. The brothers were prepared beforehand with an answer, when he inquired what they wanted of him. They replied immediately that the shock of their father’s horrible death had so seriously affected their aunt and their eldest sister, that it was feared the minds of both might give way, unless spiritual consolation and assistance were afforded to them that night. The unhappy priest—always faithful and self-sacrificing where the duties of his ministry were in question—at once rose to accompany the young men back to the house. He even put on his surplice, and took the crucifix with him, to impress his words of comfort all the more solemnly on the afflicted women whom he was called on to succour.

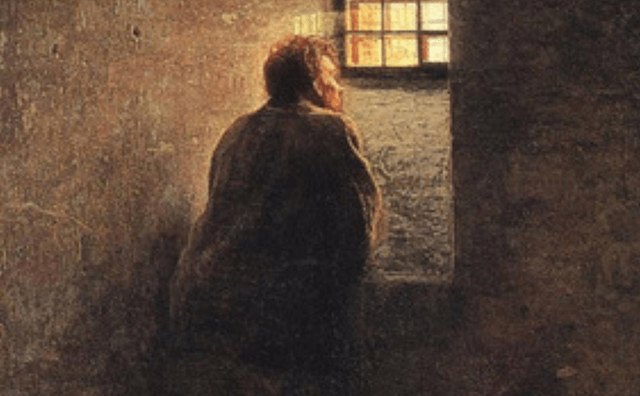

Thus innocent of all suspicion of the conspiracy to which he had fallen a victim, he was taken into the room where Jean sat waiting by the cauldron of oil; and the door was locked behind him.

Before he could speak, Thomas Siadoux openly avowed the truth.

“It is we three who want you,” he said—”not our aunt, and not our sister. If you answer our questions truly, you have nothing to fear. If you refuse——” He stopped, and looked toward Jean and the boiling cauldron.

Never, at the best of times, a resolute man; deprived, since the day before, of such resources of energy as he possessed, by the mental suffering which he had undergone in secret—the unfortunate priest trembled from head to foot, as the three brothers closed round him. Louis took the crucifix from him, and held it; Thomas forced him to place his right hand on it; Jean stood in front of him and put the questions.

“Our father has been brought home a murdered man,” he said. “Do you know who killed him?”

The priest hesitated; and the two elder brothers moved him nearer to the cauldron.

“Answer us, on peril of your life,” said Jean. “Say, with your hand on the blessed crucifix, do you know the man who killed our father?”

“I do know him.”

“When did you make the discovery?”

“Yesterday.”

“Where?”

“At Toulouse.”

“Name the murderer.”

At those words, the priest closed his hand fast on the crucifix, and rallied his sinking courage.

“Never!” he said firmly. “The knowledge I possess was obtained in the confessional. The secrets of the confessional are sacred. If I betray them, I commit sacrilege. I will die first!”

“Think!” said Jean. “If you keep silence, you screen the murderer. If you keep silence, you are the murderer’s accomplice. We have sworn over our father’s dead body to avenge him—if you refuse to speak, we will avenge him on you. I charge you again, name the man who killed him.”

“I will die first,” the priest reiterated, as firmly as before.

“Die then!” said Jean. “Die in that cauldron of boiling oil.”

“Give him time,” cried Louis and Thomas, earnestly pleading together.

“We will give him time,” said the younger brother. “There is the clock yonder, against the wall. We will count five minutes by it. In those five minutes, let him make his peace with God—or make up his mind to speak.”

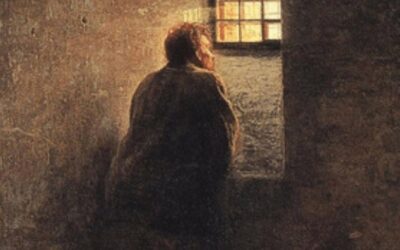

They waited, watching the clock. In that dreadful interval, the priest dropped on his knees and hid his face. The time passed in dead silence.

“Speak! for your own sake, for our sakes, speak!” said Thomas Siadoux, as the minute hand reached the point at which the five minutes expired.

The priest looked up—his voice died away on his lips—the mortal agony broke out on his face in great drops of sweat—his head sank forward on his breast.

“Lift him!” cried Jean, seizing the priest on one side. “Lift him, and throw him in!”

The two elder brothers advanced a step—and hesitated.

“Lift him, on your oath over our father’s body!”

The two brothers seized him on the other side. As they lifted him to a level with the cauldron, the horror of the death that threatened him, burst from the lips of the miserable man in a scream of terror. The brothers held him firm at the cauldron’s edge. “Name the man!” they said for the last time.

The priest’s teeth chattered—he was speechless. But he made a sign with his head—a sign in the affirmative. They placed him in a chair, and waited patiently until he was able to speak.

His first words were words of entreaty. He begged Thomas Siadoux to give him back the crucifix. When it was placed in his possession, he kissed it, and said faintly, “I ask pardon of God for the sin that I am about to commit.” He paused; and then looked up at the younger brother, who still stood in front of him. “I am ready,” he said. “Question me, and I will answer.”

Jean repeated the questions which he had put, when the priest was first brought into the room.

“You know the murderer of our father?”

“I know him.”

“Since when?”

“Since he made his confession to me yesterday, in the cathedral of Toulouse.”

“Name him.”

“His name is Cantegrel.”

“The man who wanted to marry our aunt?”

“The same.”

“What brought him to the confessional?”

“His own remorse.”

“What were the motives for his crime?”

“There were reports against his character; and he discovered that your father had gone privately to Narbonne to make sure that they were true.”

“Did our father make sure of their truth?”

“He did.”

“Would those discoveries have separated our aunt from Cantegrel if our father had lived to tell her of them?”

“They would. If your father had lived, he would have told your aunt that Cantegrel was married already; that he had deserted his wife at Narbonne; that she was living there with another man, under another name; and that she had herself confessed it in your father’s presence.”

“Where was the murder committed?”

“Between Villefranche and this village. Cantegrel had followed your father to Narbonne; and had followed him back again to Villefranche. As far as that place, he travelled in company with others, both going and returning. Beyond Villefranche, he was left alone at the ford over the river. There Cantegrel drew the knife to kill him, before he reached home and told his news to your aunt.”

“How was the murder committed?”

“It was committed while your father was watering his pony by the bank of the stream. Cantegrel stole on him from behind, and struck him as he was stooping over the saddle-bow.”

“This is the truth, on your oath?”

“On my oath, it is the truth.”

“You may leave us.”

The priest rose from his chair without assistance. From the time when the terror of death had forced him to reveal the murderer’s name, a great change had passed over him. He had given his answers with the immoveable calmness of a man on whose mind all human interests had lost their hold. He now left the room, strangely absorbed in himself; moving with the mechanical regularity of a sleep-walker; lost to all perception of things and persons about him. At the door he stopped—woke, as it seemed, from the trance that possessed him—and looked at the three brothers with a steady changeless sorrow, which they had never seen in him before, which they never afterwards forgot.

“I forgive you,” he said, quietly and solemnly. “Pray for me, when my time comes.”

With those last words, he left them.

IV. The End.

The night was far advanced; but the three brothers determined to set forth instantly for Toulouse, and to place their information in the magistrate’s hands, before the morning dawned.

Thus far, no suspicion had occurred to them of the terrible consequences which were to follow their night-interview with the priest. They were absolutely ignorant of the punishment to which a man in holy orders exposed himself, if he revealed the secrets of the confessional. No infliction of that punishment had been known in their neighbourhood—for, at that time, as at this, the rarest of all priestly offences was a violation of the sacred trust confided to the confessor by the Roman Church. Conscious that they had forced the priest into the commission of a clerical offence, the brothers sincerely believed that the loss of his curacy would be the heaviest penalty which the law could exact from him. They entered Toulouse that night, discussing the atonement which they might offer to Monsieur Chaubard, and the means which they might best employ to make his future life easy to him.

The first disclosure of the consequences which would certainly follow the outrage they had committed, was revealed to them when they made their deposition before the officer of justice. The magistrate listened to their narrative with horror vividly expressed in his face and manner.

“Better you had never been born,” he said, “than have avenged your father’s death, as you three have avenged it. Your own act has doomed the guilty and the innocent to suffer alike.”

Those words proved prophetic of the truth. The end came quickly, as the priest had foreseen it, when he spoke his parting words.

The arrest of Cantegrel was accomplished without difficulty, the next morning. In the absence of any other evidence on which to justify this proceeding, the private disclosure to the authorities of the secret which the priest had violated, became inevitable. The Parliament of Languedoc was, under these circumstances, the tribunal appealed to; and the decision of that assembly immediately ordered the priest and the three brothers to be placed in confinement, as well as the murderer Cantegrel. Evidence was then immediately sought for, which might convict this last criminal, without any reference to the revelation that had been forced from the priest—and evidence enough was found to satisfy judges whose minds already possessed the foregone certainty of the prisoner’s guilt. He was put on his trial, was convicted of the murder, and was condemned to be broken on the wheel. The sentence was rigidly executed, with as little delay as the law would permit.

The cases of Monsieur Chaubard, and of the three sons of Siadoux, next occupied the judges. The three brothers were found guilty of having forced the secret of a confession from a man in holy orders, and were sentenced to death by hanging. A far more terrible expiation of his offence awaited the unfortunate priest. He was condemned to have his limbs broken on the wheel, and to be afterwards, while still living, bound to the stake, and destroyed by fire.

Barbarous as the punishments of that period were, accustomed as the population was to hear of their infliction, and even to witness it, the sentences pronounced in these two cases dismayed the public mind; and the authorities were surprised by receiving petitions for mercy from Toulouse, and from all the surrounding neighbourhood. But the priest’s doom had been sealed. All that could be obtained, by the intercession of persons of the highest distinction, was, that the executioner should grant him the mercy of death, before his body was committed to the flames. With this one modification, the sentence was executed, as the sentence had been pronounced, on the curate of Croix-Daurade.

The punishment of the three sons of Siadoux remained to be inflicted. But the people, roused by the death of the ill-fated priest, rose against this third execution, with a resolution before which the local government gave way. The cause of the young men was taken up by the hot-blooded populace, as the cause of all fathers and all sons; their filial piety was exalted to the skies; their youth was pleaded in their behalf; their ignorance of the terrible responsibility which they had confronted in forcing the secret from the priest, was loudly alleged in their favour. More than this, the authorities were actually warned that the appearance of the prisoners on the scaffold would be the signal for an organised revolt and rescue. Under this serious pressure, the execution was deferred, and the prisoners were kept in confinement until the popular ferment had subsided.

The delay not only saved their lives, it gave them back their liberty as well. The infection of the popular sympathy had penetrated through the prison doors. All three brothers were handsome, well-grown young men. The gentlest of the three in disposition—Thomas Siadoux—aroused the interest and won the affection of the head-gaoler’s daughter. Her father was prevailed on at her intercession to relax a little in his customary vigilance; and the rest was accomplished by the girl herself. One morning, the population of Toulouse heard, with every testimony of the most extravagant rejoicing, that the three brothers had escaped, accompanied by the gaoler’s daughter. As a necessary legal formality, they were pursued, but no extraordinary efforts were used to overtake them: and they succeeded, accordingly, in crossing the nearest frontier.

Twenty days later, orders were received from the capital, to execute their sentence in effigy. They were then permitted to return to France, on condition that they never again appeared in their native place, or in any other part of the province of Languedoc. With this reservation they were left free to live where they pleased, and to repent the fatal act which had avenged them on the murderer of their father at the cost of the priest’s life.

Beyond this point the official documents do not enable us to follow their career. All that is now known has been now told of the village-tragedy at Croix-Daurade.

Wilkie Collins Books to Read

Narrated by Meridiculous, courtesy of Libravox.

If you enjoyed The Cauldron of Oil by Wilkie Collins, check out An Italian Dream By Charles Dickens