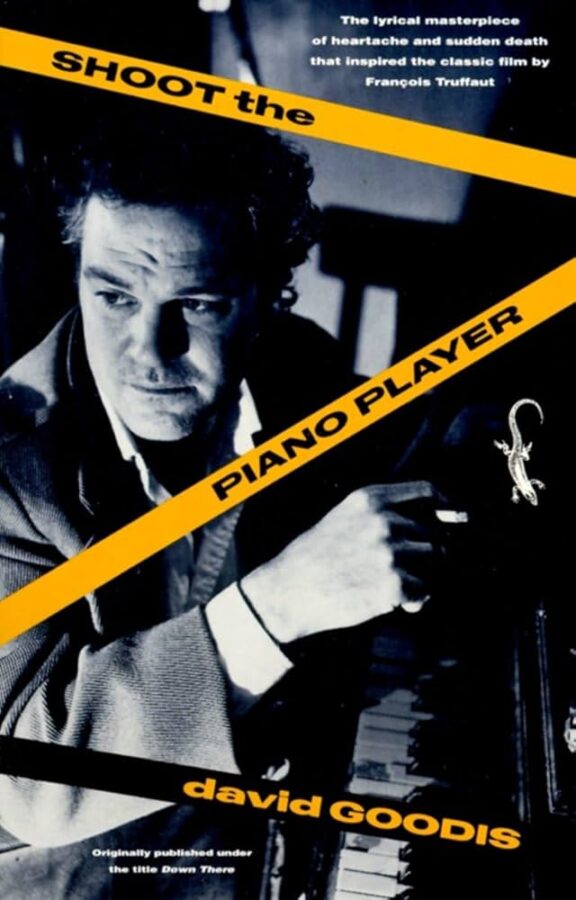

Three Guesses by David Goodis was published in the magazine Hooded Detective in 1942. It tells the story about a Private Investigator fishing for clues to the murder of a lawyer.

This post may contain affiliate links that earn us a commission at no extra cost to you.

Three Guesses by David Goodis

Three Guesses by David Goodis

It was one of those white stone places up in the east seventies. Plenty of class, Frey thought as he walked up the steps. He turned and looked at the guy waiting in the car. He shrugged, and the guy shrugged back.

Frey was in his early thirties. He was five eight and he weighed 170 and it was packed in like steel. He was a private dick and he was reckless. It showed in his grey eyes and the glint in his carelessly combed light brown hair and the set of his jawline. It showed in the thin grin of his lips.

His lips grinned like that as the door opened. A servant, a Jap.

“Yes, please?”

“I’d like to see Miss Rillette.”

“She busy.”

“Not too busy to see me,” Frey said. “I’m coming in.”

Japs are either very tough or they are very timid, and the servant was of the latter stamp. He stepped aside and Frey walked through a pale orange room, then through a burnt orange room and then into another pale orange room.

“Nice place you’ve got here, Miss Rillette,” Frey said.

She was small and slim and even in the frock of a sculptress she looked delicate and graceful. In one hand she held a chisel. In the other she held a mallet. She was working on a chunk of marble and she had the forehead and general scalp contours almost completed.

When she turned around she showed a good looking set of features. She had dark brown hair coming in bangs to the eyebrows, and her eyes were gold-hazel. Her mouth was a little too wide, but still she was a good looking girl. She was in her late twenties.

“Just who are you and what is the meaning of this?” she said.

“My name is Frey, and I’m a friend of Harry Duggin.”

“Is that so?” she said. “How is Harry?”

“He’s dead.”

She blinked a few times and then she said, “What happened—and when?”

Frey said, “He was murdered—this morning. Knifed.”

She blinked a few more times and then she looked at the floor for a few seconds. Frey was watching her and then he was glancing sideways to a little jade box that held cigarettes. He took one up, eased a stray safety match from his vest pocket, flicked it with his fingernail, and lit up.

He took a few deep drags and said, “I got an idea that you know something, Miss Rillette.”

Her face showed no emotion as she said, “I thought you said you were a friend of Harry’s. You sound more like a detective.”

“That’s right. Harry was a good friend of mine. We went to law school together. He became a successful corporation lawyer and I starved for a while and then I became a private detective. I lost touch with Harry for a year or so and then last week he called me up and asked me to do a favor for him. He asked me to follow you.”

She said, “Indeed?”

“That’s right. He must have been looking around for a private dick and then he found out that I was in business and he asked me to follow you. He said that in return for the favor he would give me one hundred and fifty bucks. So you see, Miss Rillette, I have nothing against you personally. I just have to make a living, that’s all.”

“Why did he want you to follow me?”

“You don’t have to ask me that, Miss Rillette. You know the answer. In fact, you know all the answers. I found that out through seven days of following you.”

She blinked some more and then she reached out to the little jade box and took a cigarette. Frey flicked one of his safety matches with his fingernail and gave her a light.

“What am I supposed to say?” she murmured.

He knew he was going to have trouble with this girl.

“You don’t have to say anything. I’ll write out a confession outline and you sign it. If you want to, you can fill all the gaps. But what I want most is a signed confession—”

“What did you say you were?” she murmured.

“A private detective.”

“Beginner, aren’t you?”

That made him sort of sore. But he swallowed it and said, “Maybe, but I’m not an amateur. I make a living out of this.”

She blinked and dragged half-heartedly at the cigarette and then she turned and looked at the marble she was doing. She looked back at Frey and her eyes were tired as she said, “How close did you follow me?”

“Here’s what you did,” Frey said. “On Sunday you attended an exhibition at the Wheye Galleries, up on 57th Street. From there you went to Larry’s, in the Village, where you had a dinner engagement with a man named Lasseroe. From there this guy took you to a party at the Vanderbilt. He went home alone. You stayed at the Vanderbilt. You stayed there for five days, with your very good friend, Daisy Hennifer, the jewelry designer. You had a few luncheon and dinner engagements with Lasseroe. You went to a few shops with Daisy. Then early last night you left the Vanderbilt and I lost you in Fifth Avenue traffic. I went back to tell Harry about it and to get your home address, because in all the days I’d been following you—well, you didn’t once touch home. When I got to Harry’s apartment, his valet informed me that Harry was out for the evening.”

“That’s as far as you got?”

“Hardly. I went to Harry’s apartment again this morning. The valet came to the door and told me that Mr. Duggin was sleeping. I explained that it was certainly most important and I went in. But I couldn’t wake Harry up, because he was dead. I don’t know why I’m telling you all this. You know it already.”

“How did you get my home address?” She was still blinking a lot, but she wasn’t excited.

“The valet gave it to me.”

“You told him—?”

“I didn’t tell him anything. I came out of the bedroom and told him that Mr. Duggin was still sleeping. Then I asked him for your address. Maybe he still thinks that Harry is asleep. Or maybe he’s found out already and the police are in on the case.”

She looked at the ceiling and then she looked at the floor and then she looked at Frey and said, “Now let me understand this. You say that I murdered Harry. You want me to sign a confession.”

“That’s all there is to it,” he said.

“You’re going to place yourself in a lot of difficulty, Mr. Frey,” she murmured. “I advise that you give this matter a little more thought before you accuse anyone else—”

“I’m not accusing anyone else,” Frey said. “What are you going to do?”

She blinked and then she looked at her wrist watch and then she looked at the marble. “I have a lot of work to finish before three thirty this afternoon,” she said. “Please go now.”

She turned, took up her mallet and chisel, and started to work on the marble. She acted as if Frey had already walked out of the pale orange room.

He shrugged and walked out.

The Jap servant followed him to the door. He said to the Jap, “Tell Miss Rillette that I’ll be back—after three thirty.”

He walked down the steps and stepped into the parked coupe.

He turned the key in the ignition lock and said, “No go.”

“What happened?” this other guy said. This other guy was Mogin. He was about as tall as Frey and he weighed a little over 200 pounds. He had close-cropped blond hair and pretty blue eyes and he was a very tough boy.

“She don’t know from nothing,” Frey said. He took the car around the corner and stepped on the gas.

“What do we do now?” Mogin said.

“Well, we could go to a double feature and kill the afternoon that way. Or we could go up and visit this Lasseroe.”

Mogin shrugged.

It was a new apartment house near Morningside Heights. It was elegant and smooth and important.

“Do I wait?” Mogin said.

“Maybe you better come in with me.”

They went in and rang Lasseroe’s number and he must have been expecting somebody because he buzzed an answer right away and the door opened. When Frey and Mogin stepped out of the elevator, Lasseroe was standing at the door of his apartment and when he saw them he expected them to walk right by. But they came up to him.

He was a man of medium height and he had a good build for a man of forty-five. He had a square, rigid-boned face, and deep-set dark grey eyes, and a good head of black hair threaded with silver. He was wearing a long collared silk shirt and an expensive cravat and an expensive silk lounging robe.

“Hello, Lasseroe,” Frey said.

“I beg your pardon—”

“You don’t have to beg anybody’s pardon,” Frey said. “All you have to do is answer a few questions. If you don’t mind we won’t waste time out here in the hall. We’ll go into your room and talk.”

“I presume you are thieves?” Lasseroe said. He wasn’t excited.

“No, we ain’t thieves and we don’t like funny boys,” Mogin said.

Lasseroe walked into the apartment and Frey and Mogin followed.

“Now, gentlemen?”

“My name is Frey. This is my assistant, Mr. Mogin.”

Lasseroe ignored Mogin. He said, “What do you want with me?”

Frey began to talk. He didn’t look at Lasseroe. He looked out the window and talked slowly, taking his time. He said, “You got a nice business, Mr. Lasseroe. You are an expert appraiser of art, and you take good fees from various dealers. Sometimes you hit healthy money. You check up on a Rembrandt and you give your okay to a buyer and the dealer gives you a sweet kick-back. It is all very legitimate and lucrative—”

“What are you, a census taker?” Lasseroe said.

“Quiet,” Mogin toned.

“A short time ago you figured out a few new angles,” Frey said. “You weren’t doing so good on the old stuff and you reasoned that you might be able to make up for the deficiency by a few transactions with the modern boys and girls.”

“Just what do you mean by—”

“Quiet,” Mogin toned.

“So here’s what you did,” Frey said. “You rounded up several of the more snooty painters and sculptors—the artistic boys and girls who have a lot of dough because their parents or some uncle or somebody had a lot of dough. You told the suckers that you’d boost their work in return for tribute. Then you went to the dealers and told them that you had several sensational new artists whose work would bring high prices. You’d give that work a big build-up in return for the kick-backs. It worked.”

“Now just a moment—”

“Quiet,” Mogin toned.

“Everybody was happy,” Frey said, “because nobody really lost out. The artists made dough and the dealers made dough and the customers thought they were getting high class stuff. One of these customers was Harry Duggin, the successful corporation lawyer.”

Lasseroe opened his mouth to say something. Then he closed it and looked at Frey and looked at Mogin and looked at Frey again.

“You sold Duggin a few pieces of sculpture done by a girl named Tess Rillette,” Frey said. “Duggin liked the sculpture and he wanted to meet the girl. You introduced him to Tess and he went crazy. He worshipped her. He asked her to marry him. She thought it was funny and she told you about it. You didn’t think it was funny. You saw a new dodge—”

“Now damn you—”

“Quiet,” Mogin toned.

“Duggin was out of his head because of Tess Rillette. And of course he bought up every piece of sculpture that Tess turned out. This sort of thing went on for more than a year, and Harry didn’t know that sculpture takes a long time and a high-class artist can turn out so many pieces and no more in a certain period. In other words, Harry didn’t stop to figure that you were selling him stuff that Tess Rillette had nothing to do with. That is—he didn’t stop to figure about it until he found out that Tess had fallen for you.”

“Now you look here—”

“Quiet,” Mogin toned.

“Harry could be clever when he wanted to be, and he was always clever when he was good and burned up. He checked up on that stuff you sold him, found out that it was phoney. He got in touch with you, told you that you were slated for jail—but that you could snake your way out of it—by giving up those happy little plans for yourself and Tess Rillette. By that time, you were serious about Tess and you wouldn’t give her up for anything. So you went and murdered Harry Duggin.”

“What?”

“I said—you murdered Harry Duggin.”

Lasseroe stared at the lavender rug. He raised his eyes and said, “Is Harry—dead?”

Frey reached in his pocket and pulled out a safety match and flicked it with his fingernail. Then he remembered he had no cigarette in his mouth and he reached out and Mogin took out a pack and gave him one. He lit the cigarette and he said, “I’m a detective, Lasseroe. I’d like you to tell me how you did it.”

“I didn’t do it.”

“No?” Frey looked at Mogin. Mogin shrugged.

“No, I didn’t do it,” Lasseroe said. “Let me see your badge.”

“I don’t have a badge. I’m a private detective.”

Lasseroe said, “I’ve a good mind to call the police.”

“You don’t have to call them,” Fry said. “They’ll be here soon anyway.” He walked to the door. Mogin followed.

Lasseroe stood there in the center of the lavender rug. He said, “You gentlemen have wasted your time.”

“Quiet,” Mogin toned.

In the elevator Frey said, “Maybe we can still make that double feature.”

“I’m getting hungry,” Mogin said. “How about some lunch?”

Frey parted his lips and the cigarette fell from his mouth. He stepped on the stub and said, “We’ll have lunch and then we’ll visit another party.”

“No double feature?” Mogin said.

“No double feature. We’ll visit this third party and if we strike out we’d better leave town for a few days to avoid a lot of aggravation. See what I mean?”

“I see what you mean,” Mogin said. “Who do we see now?”

“We see Daisy Hennifer, the jewelry designer,” Frey said. “We go to the Vanderbilt Hotel.”

They faked a story that they were representatives of a big Manhattan lapidary. That got them up to Daisy Hennifer’s suite. It was topaz yellow, ceiling, walls, rugs and furniture—all topaz yellow. Daisy had on a topaz yellow gown and she had topaz yellow hair.

“You won’t be able to stay long, gentlemen,” she said. “I’ve a cocktail engagement at hof post threh—”

“What’s that again?” Mogin said.

“Skip it,” Frey said.

Daisy was frowning.

“What did you do last night, Miss Hennifer?” Frey said.

Her topaz eyes started to glow and she said, “Just what do you mean by coming up here and—”

“Don’t get excited, Miss Hennifer. We’re just doing our job, that’s all.”

“But you said you were—”

“No, we don’t represent a lapidary. We’re just up here to ask you a few questions, that’s all.”

“You’re not police—” She was wearing four rings and she was twisting them about her fingers. They were all big yellow topaz stones.

“Not exactly—” Frey said.

“Well then—”

“Do you know Harry Duggin?” Frey said.

“Why—yes. In fact, I was to see him this afternoon—”

“You won’t see him, Miss Hennifer,” Frey said. “He was murdered this morning.”

“Oh—”

“He was a fine sort, Miss Hennifer. You shouldn’t have done it.”

“Done what?”

“Killed him.”

She was twisting the topaz rings. They circled fast about her long fingers, the nails of which held topaz yellow polish.

“You’ve been friends with Harry for a long time, Miss Hennifer,” Frey said. “As far as you were concerned, it was more than friendship. You went for Harry. But he wasn’t serious. And he finally gave you up altogether because he was getting big ideas concerning Tess Rillette. You hated Tess. You had known her for some time and you had paid no particular attention to her, except to laugh behind her back. You looked upon her as a girl with a lot of money and no brains and no real ability as a sculptress. When you saw her at teas and parties you just saw her, that was all. But when Harry fell for her, you had to pay attention, and you hated her. You—”

“How do you know this? Who are you? What—?”

“Please be quiet and listen,” Mogin droned.

“It was sort of natural that you should begin to cultivate this Tess Rillette’s friendship. You wanted to talk to her about Harry. You wanted to find out just how much she cared for the guy. And then you found out that she didn’t go for him at all. She adored another man. That made you hate Harry. But at the same time you still weren’t giving up hope. You went to Harry, told him that Tess Rillette was after another man. You begged him to marry you. But instead of helping the situation, your visit made things worse. Harry began to look into the matter. He found out about Tess and this man Lasseroe. He wanted to make doubly sure. He was worried about a lot of things. He had a private investigator follow Tess around during this past week.”

Mogin threw a cigarette. Frey caught it and flicked a safety match with his fingernail.

Daisy Hennifer was saying, “All this—it’s—I don’t know what to think. I don’t know what to say.”

“You don’t have to say anything,” Frey said. “Just write me a confession note, that’s all. Just write out the confession and sign it and you won’t have to say anything.”

“But—but—”

“It was convenient for you, Miss Hennifer. Lasseroe had a good motive for killing Duggin. So did Tess Rillette. At first she was indifferent to Harry. And after he threatened to have Lasseroe jailed, she hated him. But your feelings were even stronger. It was your kind of hate that turned to murder.”

“You’re wrong,” she said. She was excited. “I didn’t do it.”

“A confession will get you off easy.”

“I’m not signing any confession,” she said. “I didn’t do it. I had nothing to do with it. I adored Harry. I—”

“You’ll save yourself a lot of misery—”

She started to sob. “I didn’t do it. I—”

Frey looked at Mogin. The short, heavy guy shrugged.

“Is that all, Miss Hennifer?” Frey asked.

“That’s all I’ve got to say.” She stopped sobbing. Her topaz eyes were dull now. “Are you going to take me away?”

Frey shook his head. “We can’t take you away. We’re not cops.”

She stared. “Then—what are you?”

Frey shrugged. “Maybe we’re just a couple of damn fools.”

He nodded to Mogin. They went out of Daisy Hennifer’s suite.

They were walking toward the coupe. Mogin was saying, “It’s almost three.”

“We’ll have something to eat and we’ll go back and sit in the coupe and wait a while,” Frey said. He put his hand in his change pocket and took out two half dollars, three quarters, six dimes, four nickels. “We’ll eat a classy lunch on this,” he said. “Then we’ll wait around for a little while and we’ll see where Daisy Hennifer goes.”

“It’s all right with me,” Mogin said: “Anything’s all right with me—as long as we eat.”

They lunched at the hotel and then they walked out to the lobby and sat down and smoked. At twenty past three, Daisy Hennifer walked through the lobby and Frey and Mogin took their time and followed her.

A cab was waiting at the curb and Daisy got in.

The coupe followed.

Up Fourth avenue and two turns to blade through heavy uptown traffic and then down the street where Tess Rillette lived. The cab stopped outside the white stone house and Daisy got out.

The coupe went once around the block and then Frey parked it at the corner.

“This looks good,” he said.

Mogin nodded.

Frey said, “Maybe you better wait here. If I’m not out in thirty minutes maybe you better come in and see what’s happened to me.”

Mogin said, “Maybe you better take this.” He reached in his coat pocket and pulled out a little pistol. Frey looked at it and made a face.

“I hate to use those things.”

He took the pistol and put it in his pocket and walked up the white stone steps. The Jap came to the door and Frey said, “Well—it’s past three thirty. Miss Rillette is expecting me, isn’t she—?”

The Jap shook his head. “Miss Rillette is busy. You must call later.”

“Tell Miss Rillette that I—” He braked his tongue and said, “No—don’t tell Miss Rillette anything. In fact—maybe you better take a walk around the block.”

The Jap started to get excited. He said, “You were not among those invited—”

“Take a walk around the block,” Frey said. “Look, I’ll help you down the steps—” He grabbed hold of the Jap and hustled him down the steps. Mogin saw the deal and opened the door of the coupe. Frey pushed the Jap inside.

“What’s this?” Mogin said.

“A glimpse of the Far East,” Frey murmured. “Take him to a show. Take him to a dance. I don’t care what you do with him, only keep him away from the house for a while. He’ll get in my way otherwise.”

The Jap started to yell.

“Tag him,” Frey said. He looked up and down the street and he saw that it was all right. Then he heard a click and he saw Mogin’s fist bouncing away from the Jap’s chin. The Jap went to sleep.

“I’ll drive around the block a few times,” Mogin said.

Frey went up the steps again and took his time going through the pale orange room, the burnt orange room. Then he was moving slowly and very quietly as he heard voices coming from the other pale orange room. The orange door was closed but Frey managed to get in a look through the side windows of the studio. The windows were slits of glass running from the floor to the ceiling, and through them Frey saw Tess Rillette and Lasseroe and Daisy Hennifer.

They were all talking at once and at first their voices were low but then they started to argue and Frey got in on it.

“Clever, weren’t you, Daisy?” Tess Rillette was saying. “You asked me to be your guest at the hotel, and I thought it was hospitality. But what you really wanted was to keep me away from here. You didn’t want Harry to get in touch with me.”

“That’s a lie,” Daisy said. “I asked you to stay at the hotel purely for business reasons. I wanted you to work on those inlaid ivories—”

“That’s what I thought—at first,” Tess Rillette said. “But I know the truth now. You wanted to keep me away from Harry. You thought maybe you had one last chance of winning him back. And when you found out it was futile—you killed him!”

“She’s right, Daisy,” Lasseroe said. “You killed Harry Duggin. You worshipped him—and hated him!”

He got out of the chair and pointed at her, and a few glasses on a cocktail tray tipped over.

Daisy was shouting, “You’re both lying! You’re trying to place the blame on me and switch things around so that I’ll be put out of the way. You’re trying to commit—double murder!”

“Just what do you mean by that?” Lasseroe said.

Daisy’s voice was lowered as she stared at the art appraiser and said, “You killed him. You had every reason to kill him, and you did it. And now you’re trying to get me out of the way. I know the truth about you, Lasseroe. I know how you’ve been swindling art patrons, charging them exorbitant prices for cheap junk such as Tess puts out—”

Tess Rillette wasn’t taking this sitting down. She started to call Daisy a lot of nasty names. It was all very unpleasant.

And then Lasseroe said, “You’ve got a lot of influence around this town, haven’t you, Daisy?”

She liked that. She nodded. And there was a mean smile on her lips. Lasseroe was moving slowly toward her, and his face was pale. There was a light in the man’s eyes that told Frey a lot of things. Frey reached into his coat pocket and touched the revolver to make sure that it was still there.

“You’ve got a lot of mouth, too,” Lasseroe was saying.

“Just what do you mean by that?” Daisy looked at him straight.

“You may turn out to be quite an annoyance,” Lasseroe said. He kept moving toward her.

Tess Rillette was grabbing Lasseroe’s arm, saying, “Please—enough has already happened—”

But Lasseroe was excited and he was pushing Tess Rillette away and then he was making a grab for Daisy. She fell backward and he went over with her and he got his fingers around her throat. She managed to scream once and then she started to gurgle. Frey opened the door and took out his revolver and pointed it at Lasseroe’s spine.

“All right,” he said, “Let’s stop playing.”

But Lasseroe was out of control now and he was choking the life out of Daisy Hennifer. He didn’t seem to hear Frey, and he increased the pressure of his fingers around Daisy’s windpipe. Tess Rillette was screaming and putting herself between Frey and Lasseroe, in an ungraceful try at the old martyr act.

Frey knew that he couldn’t stand on ceremony. He had to break it up and break it up fast. He pushed Tess Rillette and she didn’t like being pushed. She was screaming now, and she threw fingernails at his face. He let her have a slow right to the jaw and it sent her across the room, spinning.

Then he had a try at Lasseroe.

He tried to pull Lasseroe away from Daisy Hennifer, who by now was in a very bad way. But Lasseroe was a maniac now and he wanted to take the life away from the jewelry designer. Frey knew that he would have to use the revolver. He lifted it and then allowed the butt to come down and make contact with Lasseroe’s skull.

Lasseroe went to sleep.

“We’ll take them all down to Harry’s apartment,” Frey said. “If the cops aren’t there already, it’ll be a good idea to finish the case right on the spot where it started.”

“That’s a very good idea,” Mogin said. “I have a hunch that this will put us on the map.”

Frey nodded. He prodded Lasseroe with the revolver and said, “You and Miss Rillette will sit in the opera seats with me. Miss Hennifer will ride in front.” He touched the shivering Jap on the elbow and said, “The studio is in quite a bad state. Better go in there and rearrange things. If you have any questions to ask Miss Rillette, maybe you better call the police station. That’ll be her temporary address before she goes away on a long trip.”

He stepped into the coupe and closed the door. Lasseroe was manacled to him and Miss Rillette was manacled to Lasseroe. Daisy was still groaning as Mogin put the car in first and sent it whizzing down the street.

“You’re making a big mistake,” Lasseroe said.

“I wouldn’t talk about making mistakes if I were you,” Frey said lightly. He felt very good. All a private investigator needed was one good break like this, and he was made. The cases would come in thick and fast, and so would the dough. Frey smiled.

Tess Rillette was saying, “I told you, Mr. Frey—you were letting yourself in for a lot of difficulty, and—”

“Do I turn here?” Mogin was saying.

There were a few police cars in front of the high-class apartment where Harry Duggin had lived, and where he had died. The coupe parked across the street and Frey saw the crowd and the reporters. He said, “All right—here we go.”

Everyone was looking and murmuring as the five of them went into the apartment house. A cop walked over and said, “What’s this?”

“It’s the Harry Duggin case,” Frey said.

They stepped into the elevator and went up seven floors to the apartment. There were a lot of cops up there, a lot of plain clothes men and lads from the homicide bureau. Reporters and photographers and a doctor.

“What’s this?” a plain clothes man said.

“It’s the Harry Duggin case,” Frey said.

The mob crowded around. This little deal was taking place in the living room of the apartment. The dick was saying, “Carven is in the bedroom. He’s talking to Duggin’s valet.” He frowned at Frey and said, “What have you got?”

“Enough,” Frey said. He pointed to Lasseroe. “Here’s your baby. I’m going in and talk to Carven.”

As he started for the bedroom door he heard Lasseroe saying, “You’re making a big mistake—”

Frey smiled.

He went into the bedroom and he saw Carven, the big shot detective. He saw the two cops in there and he saw the valet, and then the corpse of Harry Duggin. Carven had the valet by the back of the neck. Carven was a big man and he was forcing the valet to look down at Harry Duggin’s dead face.

Carven was saying, “Look at him. He’s dead. Do you get that? He’s dead. You called us in here and you figured that would automatically put you out of the picture. And you told us that a guy by the name of Frey came in here this morning and killed him. But Frey’s an old pal of mine. Frey’s a private dick—a lousy one, reckless and careless, but still he’s a dick and your story didn’t go. You killed Duggin—why—why—?”

Not only was Carven big, he was plenty tough. He gave the valet a short left and a mean right to the ribs. The valet broke.

“I—I killed him,” he said, and it turned into a sob. “I—I wanted something that he owned—”

“What was it?” Carven said. He raised his head, clipped to one of the cops, “Take this down.”

The valet was sobbing, saying, “He had a fortune in little marble statues. He was always talking about those marble statues, telling me how priceless they were. He—kept talking about those statues all the time, telling me that the greatest sculptress in the world made them—and that money couldn’t buy them. That’s all he talked about—the statues made by Tess Rillette. He—drove it into me—made me crazy with the desire to own them. I—I—put a knife into him—”

Carven grinned. He looked at the cops and said, “Pretty fast, wasn’t it? We came in on this case exactly two and a half hours ago. I can well imagine what happened to that wise guy Frey. He came in here this morning and he saw Duggin lying dead in bed and he figured he’d go out with his stooge Mogin and do big things. I’d like to see his face when he finds out—”

Then he turned and saw Frey’s face.

Mogin was talking loud and fast. He was saying, “What’re you crying the blues about? It was just a bad break, that’s all. And at least we pinned something on somebody. We got that smart bird Lasseroe locked up for fake art manipulations, and—”

They were walking toward the coupe. Frey was shaking his head and his head was hanging low. He said, “Can we make a late double feature?”

“Sure,” Mogin said. He put his heavy hand on Frey’s shoulder and said, “It’s a good idea. We’ll go to the movies and get it off our minds. Don’t worry, pal. Better days are coming. Hey—where you goin’?”

Frey was walking away from the coupe, toward a corner drug store. “I’ll be right back,” he said. “I just want to go in here and take an aspirin. It’ll help me wait for the better days.”

Best David Goodis Books to Read

if you enjoyed Three Guesses by David Goodis, check out The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle by Arthur Conan Doyle

Narrated by Chris Pyle, courtesy of Librivox.